Across Europe, animals once thought lost are slowly coming back. Not through miracles, but through years of work, research, and a shift in how we think about nature. What does it take for wildlife to return?

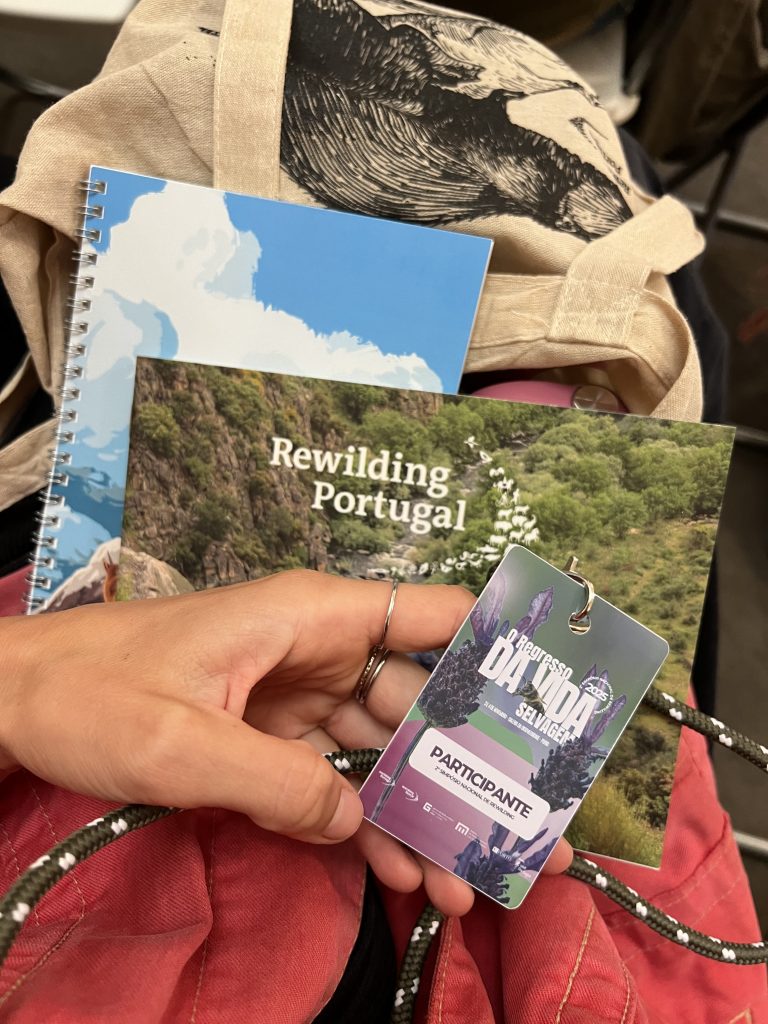

At the Portuguese National Rewilding Symposium 2025, held at Porto’s Galeria da Biodiversidade and organised by Rewilding Portugal, this question stood at the centre of the conversation. Researchers, practitioners, and conservationists from across Europe came together for two days to share experiences, challenges, and hopes under one theme: The Return of Wildlife.

The phrase sounds romantic, but the stories behind it reveal how complex and interconnected this “return” truly is.

Looking Back: The Story of Wildlife in Europe

To understand how wildlife can return, we first need to understand what we once had and how it disappeared. In this spirit the symposium opened with a journey deep into the past, exploring traces of Europe’s former megafauna. It’s a familiar theme in rewilding: looking further back than our imagination usually allows us to grasp which animals once shaped our landscapes. For many, it’s surprising to learn that animals like elephants were once a common sight in Europe.

Because we cannot easily imagine such a world, rewilders are often labelled as “unrealistic” when referencing these historical references. Yet looking that far back is crucial, as it reveals how deeply the shifting baseline syndrome, the tendency to view the state of nature in our own lifetime as “normal,” forgetting how much had already been lost before, affects our perception of nature.

Understanding the past is also about understanding how people and wildlife coexisted. Researchers use stories, cultural remains, artworks, and even place names to trace where species once lived and how humans related to them.

These relationships can reveal surprising findings. For example, as Ricardo Jorge Lopes, Researcher at the University of Lisbon, showed in his presentation on the recovery of the Purple Swamphen in Portugal, species once thought extremely rare can turn out to have been common and even beloved. Historical artworks show that this species was widespread and sometimes even kept as a pet.

Place names, too, tell stories. Across Portugal, one finds various places called “Guincho”, most likely a reference to the osprey, which the Portuguese word “guincho” denotes. The famous Guincho Beach near Lisbon is one of them. Many today wrongly explain the name as referring to the “screeching wind,” a reinterpretation born of the osprey’s long absence. While these misinterpretations give us an indication of how long this bird must already be absent in these areas and how fast our baseline shifts, such linguistic traces can help researchers identify former habitats and guide reintroduction efforts.

It’s a powerful reminder that wildlife was never separate from people. Our landscapes, our culture, even our words carry the marks of animals that once shaped them and that we, in turn, shaped too.

Bringing Them Back: Reintroduction and Breeding

Many talks moved from the historical to the practical, from the stories of what once was, to the work being done today to bring these species back.

Some species, like the Purple Swamphen, recovered quickly, adapting well to human-modified environments and even appearing on golf course ponds. Others face far greater challenges. The reintroduction of the osprey, for instance, has shown promising results, yet creating suitable nesting habitats remains difficult. Many of the cliffs and coastal sites where ospreys once nested, such as the ones near Guincho Beach, are now densely populated, and the birds are hesitant to return. Sustaining and restoring such habitats remains a key challenge.

Other species, like the Iberian lynx, face even more complex obstacles. With only a handful of individuals left on the Iberian Peninsula decades ago, their survival depended on a strong collaboration between Portugal and Spain. Rodrigo Serra, Director of the National Centre for Iberian Lynx Reproduction, shared how genetic breeding has been both the species’ greatest challenge and its only chance for recovery.

Few individuals of a species also mean that the remaining gene pool of the species is extremely small. Working with such a small gene pool brings risks, from inbreeding to genetic disorders like juvenile epilepsy, which can make individuals unfit for release or even lead to their death. Yet despite these hurdles, the Iberian lynx population is growing, a testament to persistence, science, and cross-border collaboration.

These stories remind us that behind every reintroduction lies a web of research, coordination, and care, and that much more is required than simply placing animals back into a landscape.

The Beaver’s Comeback: A Symbol of Hope and Challenge

One of the most discussed moments of the symposium was the return of the beaver, recently observed again in Portugal after centuries of absence. While its comeback wasn’t the result of a planned reintroduction, it was welcomed with excitement and optimism, and rightfully took a centre stage in the symposium.

Beavers are keystone species, species whose presence fundamentally shapes the entire ecosystems and its processes. Their absence across much of Europe for centuries meant that countless other species lost the habitats that beavers create. The ecological effects of beaver dams are complex and difficult for humans to replicate and in several European countries, beaver reintroductions have already proven invaluable for restoring wetlands and rivers.

Experts from England, Germany, and Spain spoke about the beaver’s extraordinary ability to transform landscapes, building wetlands, storing water, and creating biodiversity hotspots. In many regions, beavers have become unexpected allies of restoration practitioners, doing work that once required heavy machinery and manpower.

Yet, their return also brings challenges: flooded fields, felled trees, and altered waterways. As the speakers reminded us, coexistence with wildlife is never effortless, it must be learned and continually managed.

Still, the beaver’s return sparked hope. If a species as transformative as the beaver can make its way back, perhaps it signals that we are finally learning to make space again for nature’s own processes to take over.

Making Space Again: Restoring Habitats and Landscapes

If one message resonated throughout the symposium, it was that wildlife can only return when the landscapes are ready for them.

The discussions moved from species-specific efforts to the broader challenge of restoring habitats forests, rivers, and wetlands that form the foundation for all rewilding work. Speakers shared inspiring examples from across Portugal: river revitalisation projects, forest management approaches that reduce fire risk, and large-scale restoration efforts that strengthen ecosystems against climate change.

Restoration, as many emphasised, is not just an environmental act. It’s a social and cultural one, a way of rebuilding resilience and redefining our relationship with the land.

Humans in the Story: Conflict, Culture, and Communication

Another recurring thread throughout the symposium was the human dimension.

From legal complexities to cultural attitudes, the return of wildlife is as much about people as it is about the animals themselves. Communicating these reintroductions, changing legal frameworks to support reintroductions, involving local communities, and fostering coexistence will remain some of the greatest challenges for rewilding.

It felt fitting that the symposium was held at the Galeria da Biodiversidade, a place that embodies how to communicate the importance of biodiversity to the wider public. The permanent exhibition of the museum is a masterclass in science communication blending art, interactivity, and aesthetics. Walking through its glowing installations and sculptural displays, it became clear how creativity can make biodiversity tangible and even emotional.

Rewilding, after all, is not just a technical field. It is also a cultural one. How we talk about nature, how we represent it, and how we invite others to experience it will shape how well wildlife can truly return.

Learning from the Return

Leaving Porto, one feeling stayed: wildlife return is not a destination, it’s a relationship in the making. It requires patience, openness, humility and an understanding that humans are part of the process, not outside of it. The return of wildlife reminds us that rewilding is about more than bringing back species. It’s about restoring relationships between people, places, and the living systems we share.